On a tour to Central Mexico, we were lucky enough to be joined by Dale from The Maritime Explorer. Here he recounts his visit with us to Monte Alban.

This is my seventh post on a recent almost month long trip to the Central Highlands of Mexico with Canadian tour specialists Adventures Abroad. If you want to know more about Adventures Abroad and why you should consider their Central Mexico with Victor Romagnoli, read this post. This is also the first post on a destination outside Mexico City, the amazing centre of the Zapotec civilization, Monte Alban, which sits on a mountain top high above the colonial city of Oaxaca. I hope you’ll read on to find out why this is a must visit site for anyone with an interest in pre-Colombian Meso-America.

Who Are the Zapotecas?

Usually when one refers to an ancient people and their culture it is in the past tense, because they and their descendants are long gone, victims of the inexorable grind of history riven with wars, plagues, famines – you name it. Some people claim there’s some horsemen involved. However, the Zapotec people who have occupied the southern highlands of present day Oaxaca state since at least 700 B.C. are still around today with their own language and culture. Their numbers are relatively small in comparison to the overall population of Mexico; estimated to be around a million. But compare that to the numbers of purely Indigenous peoples of Canada which is also just over one million, but divided into hundreds of distinct tribes or nations, and you realize that the Zapotecas are a pretty significant Indigenous group.

Modern day scholars and archaeologists are in general agreement that the chronology of Meso-America, in terms of the rise and fall of civilizations that have left behind tangible evidence of their cities, religion, economy and in some cases, writings, can be divided into three periods. The first is the Pre-Classic or Formative that dates from 2000 B.C. to around 250 by which time most of the traditions generally associated with Meso-American peoples were well established. These include the building of pyramids, human sacrifice, dependence on corn, the calendar and the ritual of the ‘ball game’. The Classic period lasted from 250 to around 900 and was the heyday of the great city of Teotihuacan near Mexico City and the city we are visiting today – Monte Alban. The Post-Classic period lasted up until the arrival of the Spanish and was dominated in Central Mexico by the rise of the Aztecs and their great city of Tenochtitlan.

Perhaps uniquely among Mexican Indigenous groups the Zapotecas can be found throughout all three periods. While the Olmecs of the first period and the Toltecs and Teotihuacanos of the second are all long gone, the Zapotecas survived as a distinct people. While descendant’s of the Aztecs do survive as the Nahua people they were the new comers to the party arriving only in the Post-Classic period. To my knowledge, the only other people who could make the same claim as the Zapotecas are the Mayans.

The Rise of Monte Alban Mexico

Where present day Oaxaca sprawls for over 30 sq. miles (80 sq. kms.) was once the confluence of three valleys each with their own small distinct societies that initially fought with each other for dominance. In a process not dissimilar to what was happening in ancient Greece around the same time, gradually one group triumphed over the rest and created a larger coalition of peoples who then were able to spread their influence over an even greater area. In the case of the Zapotecs, it appears that the creation of a fortified settlement on what is today Monte Alban that was the turning point that led to the dominance of the people who built it. Like Troy, Mycenae and most famously Rome, Monte Alban was not built in a day and the ruins we we’ll see today represent the final stages of an extensive building program that spanned over five hundred years. By 200 A.D. Monte Alban controlled all of the southern highlands and considerably more territory, expanding all the way to the Pacific Ocean..

At its height, Monte Alban is believed to have had less than 20,000 people occupying the site and surrounding area. Despite these relatively modest numbers it maintained its position as the dominant city in the south highlands for five hundred more years. Interestingly, by around 700 it appears that the Zapotecs were not the rulers of Monte Alban, but rather the Mixtecas, who were reusing Zapotec tombs for some of the most elaborate burials ever found in Mexico. By the time the Spanish arrived in the 1520’s Monte Alban had been abandoned for five hundred years, although the Zapotecas were still in the area. So this place has a very, very long history.

Excavating Monte Alban

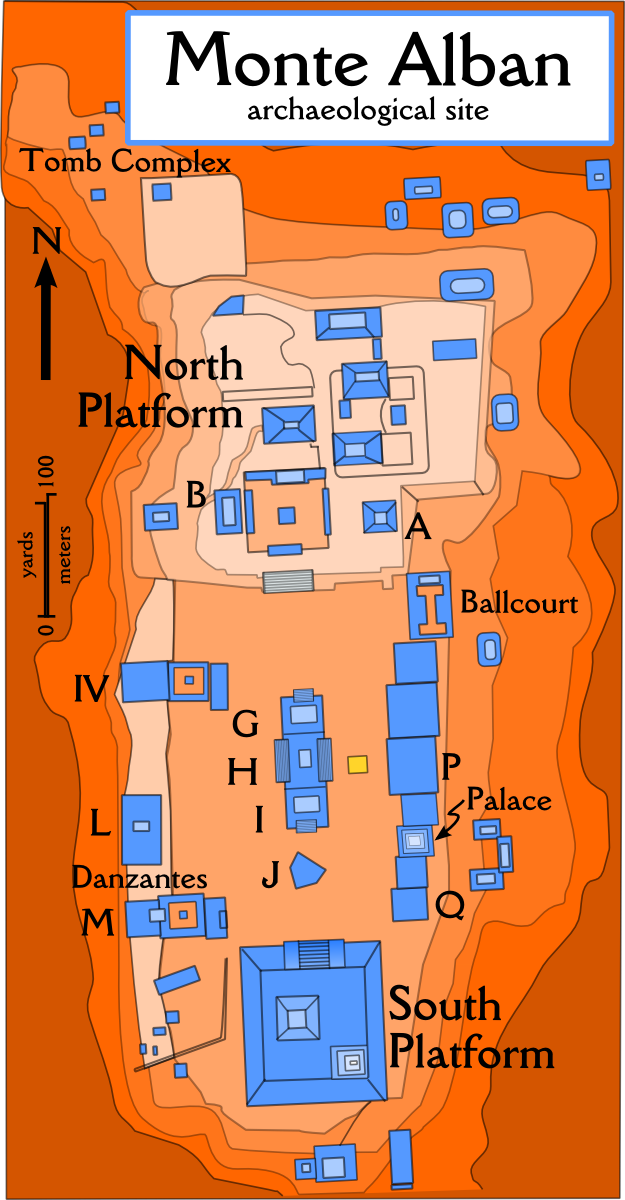

This is a map of Monte Alban as it exists today, but that was only after the painstaking work of many different archaeological teams dating back to early 20th century. Given its position in a clearly visible location above Oaxaca it was always known that a major complex once existed on Monte Alban. The most important work took place over an eighteen year period when Alfonso Caso, the Indiana Jones of Mexico, directed the excavation of the site including discovering the incredible Mixtec Tomb 7. We will see some of the artifacts from this tomb on display in the archaeological museum in Oaxaca.

Today Monte Alban, along with Oaxaca, is a UNESCO World Heritage Site with this description of its importance to mankind.

Monte Alban is the most important archaeological site of the Valley of Oaxaca. Inhabited over a period of 1,500 years by a succession of peoples – Olmecs, Zapotecs and Mixtecs – the terraces, dams, canals, pyramids and artificial mounds of Monte Albán were literally carved out of the mountain and are the symbols of a sacred topography. The grand Zapotec capital flourished for thirteen centuries, from the year 500 B.C to 850 A.D. when, for reasons that have not been established, its eventual abandonment began. The archaeological site is known for its unique dimensions which exhibit the basic chronology and artistic style of the region and for the remains of magnificent temples, ball court, tombs and bas-reliefs with hieroglyphic inscriptions. The main part of the ceremonial centre which forms a 300 m esplanade running north-south with a platform at either end was constructed during the Monte Albán II (c. 300 BC-AD 100) and the Monte Albán III phases. Phase II corresponds to the urbanization of the site and the domination of the environment by the construction of terraces on the sides of the hills, and the development of a system of dams and conduits. The final phases of Monte Albán IV and V were marked by the transformation of the sacred city into a fortified town. Monte Albán represents a civilization of knowledge, traditions and artistic expressions. Excellent planning is evidenced in the position of the line buildings erected north to south, harmonized with both empty spaces and volumes. It showcases the remarkable architectural design of the site in both Mesoamerica and worldwide urbanism.

So with that rather lengthy, but necessary introduction let’s go visit Monte Alban.

Visiting Monte Alban

I first laid eyes on Monte Alban from my window seat on the short AeroMexico flight to Oaxaca. If know what you are looking for, it is unmistakeable and this is what makes Monte Alban so unique. The builders of the final stage city literally lopped off the top of the mountain named Monte Alban to create a level playing field on which to build their monuments. Although stupidly I didn’t have my camera ready, this photo shows pretty well what I saw as we descended to the Oaxaca airport.

We boarded a bus after leaving the small Oaxaca airport and travelled through the outskirts of the city to a road that climbed and climbed and climbed until at last we reached the small virtually deserted parking lot. Usually there are vendors and hustlers at all these well known sites, but all there was here were a few old men sitting on a wall and the ever present dogs. It was a good omen for our visit.

After a short walk up hill to the entrance area we had a quick tour of the small museum with the local guide we had picked up along the way. There really is not much to see here as most of the smaller artifacts are either in Oaxaca or Mexico City. What was interesting was to see these two fellows at work on preparing the site’s Day of the Dead altar. As I’ve noted in earlier posts, every business, church, school, tourist site etc. builds one of these in late October. Most of them are real works of art that require painstaking arrangements of flowers, coloured sand and other material.

We entered the site from the northeast side and since this was our first visit to an archaeological site outside Mexico City the group was naturally curious to ask a lot of questions about the very first ruin we came to, one of those small buildings in the upper right hand corner of the map. I knew we had a limited amount of time here so I didn’t want to spend it hanging around one of the lesser building so Alison and I and a couple of others headed out on our own and spent the next two hours touring Monte Alban on our own. We did come across the main group a few times which was now being led by our tour guide Victor Romagnoli as it was apparent that he knew more about Monte Alban than the local guide – and we could understand him as well.

Alison and I made our way to the North Platform and came to the base of this stone stairway. Note the sign to the left. Monte Alban was quite well signed with most having English as well as Spanish.

Parts of Monte Alban are off limits for climbing, but the main structures you are going to want to climb are not. The stairs beckoned and we arrived at the top to see this view. Simply stunning, and where are all the people? Visiting Monte Alban without the huge crowds I knew we would find at Teotihuacan made this, for me, perhaps the most enjoyable of all the archaeological sites we visited on this tour. Plus the fantastic weather and views didn’t hurt either.

Below to the left we could see ongoing work on one of the side structures.

The view from the North Platform included the city of Oaxaca far, far below. Standing atop this structure I could understand why the people who lived in the valleys below referred to the residents of Monte Alban as “The Cloud People”.

Moving to the west side of the North Platform area you get this view of Monte Alban.

The stairs down were a lot steeper than the ones going up and you certainly needed to be careful. Rather than tackle them straight on, sidling down sideways was a lot safer and apparently the way the original constructors intended people to ascend and descend.

Once in the Central Courtyard, which is immense, you are surrounded on all sides by elevated platforms. This is looking back toward the North Platform.

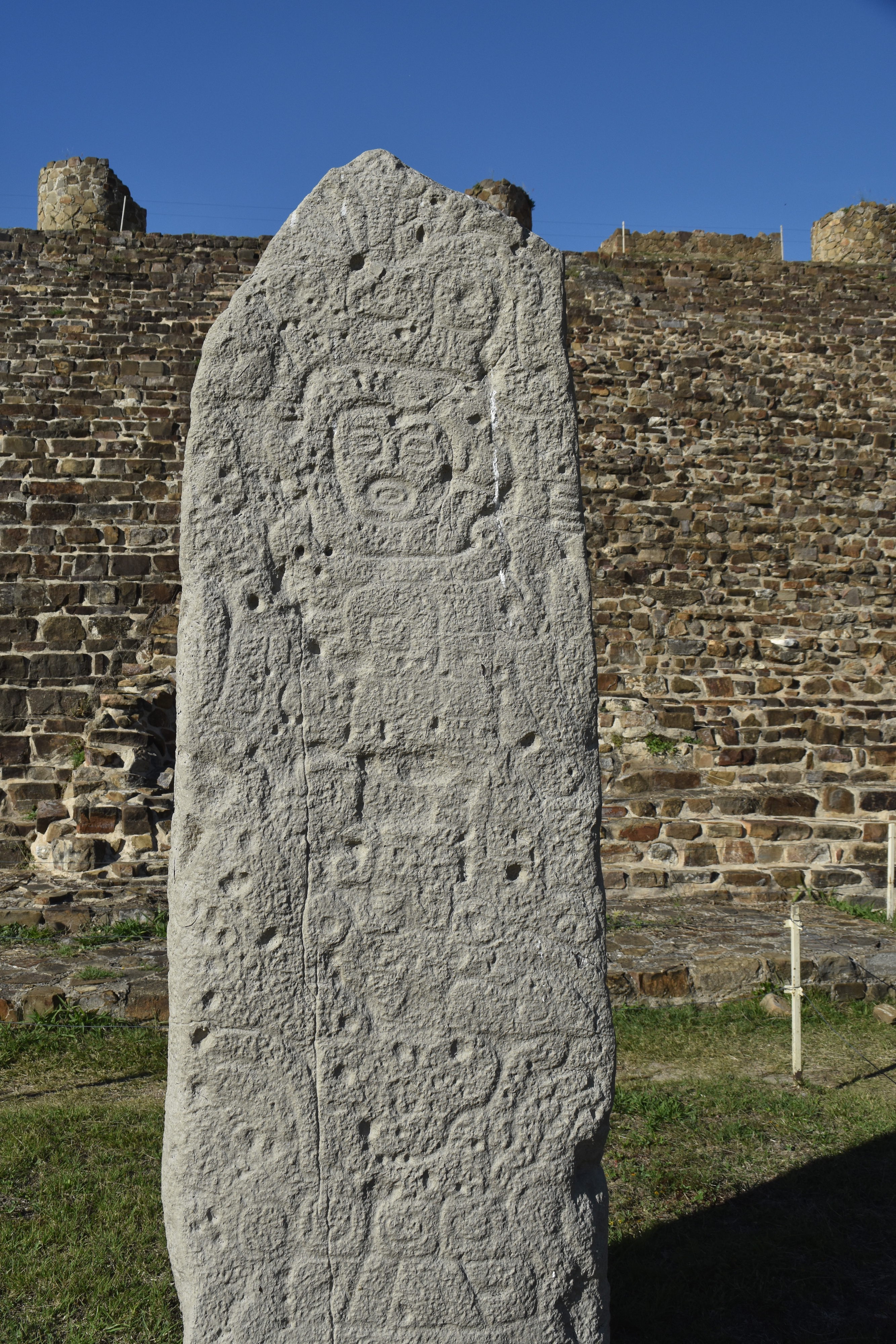

There are a number of stelae in the Courtyard at Monte Alban. This is Stela 9, one of the best preserved.

Monte Alban does not just have its ups, but is downs as well. This El Patio Hundido or the Sunken Patio.

Victor explained how this stelae, No. 19 actually was a working sun dial.

Heading towards the South Platform you pass this set of buildings which Caso simply called G,H & I.

We finally arrived at the South Platform staircase which is a lot higher and steeper than the North Platform. Alison declined to climb them, but I couldn’t resist. This is the view from the South Platform – another “Wow”. The building with the green canvas is the observatory.

Unfortunately, it was time to head back to the entrance, but the good news was that it was lunchtime and Victor ordered up a number of sharing plates at the on site restaurant which has a killer view of Oaxaca and the mountains behind.

Time to head into Oaxaca and participate in the Day of the Dead festivities.

Many thanks again to Dale for allowing us to share this post.

View all