Mexico City is such a sprawling city, that each of its districts gives a completely different feel. Join us as we discover Zocalo with Dale of The Maritime Explorer. Explore the city with Dale as Mexico City travel guide, as he explores the top sights in the city.

I’ve already written five posts on Mexico City – Templo Mayor, Xochimilco, Coyoacan, Hacienda Pena Pobre and The National Anthropological Museum and yet I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface of the myriad attractions of the capitol city. This final post will consist of my random thoughts on various places in the city, most of which are in and around the Centro Histórico which is itself, along with Xochimilco, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Please join me as we ramble around the Zócalo.

The Zócalo – Heart of Mexico City

The Zócalo is the beating heart of Mexico City to which all roads seem to converge. It is the largest plaza in the Americas and third largest in the world after Red Square in Moscow and Tiananmen Square in Peking. I visited it on a number of occasions while in Mexico City and got this one photo that makes it look relatively deserted. Trust me, that is not usually the case, especially on weekends and holidays when it is jam packed with families, tourists, church goers, buskers, beggars and umpteen vendors. Believe it or not, when it gets really busy an open space this big can actually feel claustrophobic.

The Day of the Dead festivities were under way in Mexico during my visit (in fact it was planned around that event), and the Zócalo was decorated with these great skeletons just truckin’.

That’s one cool dude in the black hat.

In addition to all the activities going on there were numerous gathering of Indigenous groups, or at least people dressed like them, who hold smudge ceremonies. For a few pesos you could buy some herbs which are then lit on fire and the smoke used to purify the purchaser. For every person doing it, there were more, like me, taking pictures of them. It looked like a good racket to be in.

Metropolitan Cathedral

Dominating one side of the Zócalo is the immense pile of stone commonly called Metropolitan Cathedral, but more properly titled Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary in Heavens. Why there is an ‘s’ on heaven I have no idea. I always assumed there was only one heaven and one hell, but what do I know. It’s only appropriate to have the largest cathedral in Latin America facing the largest plaza, but there is a price to pay for bigness. Since Mexico City is built atop a drained lake with no bedrock foundation, buildings this large literally start to sink and despite the expected protection of God and the Virgin Mary, the Metropolitan Cathedral is headed in the opposite direction of the heavens. Maybe they shouldn’t have used stolen stones from the temple of Huitzilopochtli, the Aztec god of war to start building it. Anyway, it is now claimed that nature has been conquered and the structure stabilized.

This is the very ornate entrance to the Tabernacle on the right side of the cathedral done in Latin American Baroque style which out-baroques almost anything the Europeans could come up with.

The interior was badly damaged in a 1967 fire and compared to most other churches we visited in Mexico, actually quite plain and underwhelming, except of course the altars which demonstrate the Catholic Churches’ lust for gold. This is the Altar of Forgiveness where heretics and blasphemers convicted by the Inquisition would be brought to pray for forgiveness before being executed. Unfortunately, it never worked so it really should be called the Altar of Unforgiveness.

Perhaps the most unusual thing inside the cathedral is a Foucault’s Pendulum, similar to the one in the Pantheon in Paris. The purpose is apparently to document the movement of the cathedral, but I’ll be damned if I could figure out how it was doing that.

Outside the cathedral there were two different things that I thought captured very succinctly, if not deliberately, the contradictory relationship that Mexicans have had with the church and religion in general. The first is this statue of John Paul II who visited Mexico City four times during his papacy. As papal statues go, this one is pretty good. Mexico is an avowedly secular country that has at times outright banned the Catholic Church. Even today all Catholic churches are property of the state and not the church. However, central Mexico has one of the highest rates of practising Catholics in the world – over 80% claim to follow the Vicar of Christ.

On the other side of the cathedral is this temporary exhibit built, by the congregants of the church, to commemorate the Day of the Dead. Called Muertes Altars, literally almost every church, government institution, private business and many private homes build these in late October and keep them up for weeks. There is clearly something going on here that is almost the antithesis of organized religion. It was the Aztecs, more properly Mexicas, who had the fascination with death and skulls and skeletons long before the first Spaniard set foot in Tenochtitlan. Somehow the more ancient tradition has blended with the usurper religion to create something that is neither. This was to remain an underlying theme during our entire time in Mexico and illustrated no better than the contrast at the Metropolitan Cathedral.

This idea of contrasting pre-Columbian and colonial themes can be found all over the Zócalo area if you look for it. This is one of the colonnades that surround portions of the Zócalo.

It has a series of tiles that you can see on the right side of the photo, which is not an uncommon thing to see in Mexico or Spain. One of these is the Coat-of-Arms of Mexico which adorns their flag and crops up repeatedly and yet it is a distinctly Mexica symbol that was in existence long before the Spanish arrived. You can see it etched into a large stone at the National Museum of Anthropology.

This represents a vision that the nomadic Mexica people of northern Mexico had of what they would see at the place where they would stop their wanderings and put down roots. It is a golden eagle devouring a rattlesnake that sits on a prickly pear cactus that grows on an island in the middle of a lake surrounded by mountains. That’s a lot of things that had to come together at the same time and yet both the Mexicas and many modern Mexicans believed it happened somewhere right around the Zócalo.

Not far from this tile there is modern free-standing set of sculptures depicting the same thing, but also including a group of Mexicas coming to the realization that they have found their homeland. It’s really very well done, and I could see that it also very moving to many of the Mexicans who came to view it. However, the irony that the coat-of-arms of Mexico would come from a people the Spanish decimated and despised as pagans, cannot be lost on most people.

One thing it is not uncommon to see on saint’s feast days, and there are a ton of those, is people toting large and small replicas of their particular chosen saint. This was October 28, the feast days of St. Simon and St. Jude (not Judas) who were both apostles and evangelized together after Jesus’ death.

At first glance you might think this was a statue of Jesus, but the red flames coming out of the head plus the Jesus medallion he carried to cure leprosy, give him away as St. Jude, patron saint of lost causes. One can only wonder what lost cause this fellow is hoping to have St. Jude intervene in.

The National Palace, Mexico City

No visitor to Mexico City should miss the National Palace which abuts the Zócalo on its east side. This is a public domain photo showing the exterior of the palace whose origins go as far back as Moctezuma II, the last Mexica (Aztec) king who had a palace here. Given the Spanish penchant for obliterating pre-Columbian monuments by building over them, it’s no surprise that this is where Cortés built his principal palace. Over the centuries it has been expanded many times with the current facade dating only from the 1920’s. It was the home of the viceregal rulers of New Spain followed by the President after independence. This tradition was stopped in 1884, but recently revived by current Mexican President Andrés Obrador. So it’s once again the Mexican version of the White House.

This somewhat cockeyed photo I took shows the balcony from which the President gives the annual Grito de Dolores, an event in Mexican history as important as the Declaration of Independence is to Americans. Above the balcony is a bell from the church in Dolores Hidalgo where the cry for freedom was first uttered by Miguel Hidalgo.

I have to be honest and say that when I first saw these I did not understand their significance, but after visiting many of the places associated with the War for Independence I now, belatedly, do.

The National Palace is actually a huge compound with many interior plazas and open spaces, most of which are off limits. What you are allowed inside to see is far more interesting than just the outer facade.

Entrance is free, but you need to show a passport or other government ID to get in. Once inside you can wander through the inner courtyard to the palace dating back to Cortés.

On the walls of this palace you will find Diego Rivera’s History of Mexico murals, perhaps the most famous in Mexico if not the world, for their sheer size and scope. Completed between 1929 and 1935 they depict the struggle of the Mexican people against foreign oppressors as told from a distinctly Marxist point of view. They are simply stunning and I could not believe how few people were actually here seeing them, considering that the streets outside were thronged. Unfortunately it’s next to impossible to get a good photo of the principal work that stretches across three walls and a ceiling. This is the best I could do. You can see that painting the history of an entire country in one giant painting entails a lot of characters and themes. Again, because I had not yet ventured outside Mexico City to the other places where many of the major events in Mexican history took place, I could not interpret most of what Rivera was portraying. I would like to return now that I have a much better read on Mexico and its past struggles, however, even without knowing what was going on in a lot of the scenes this work was still mesmerizing.

I was able to get a better grasp of some parts of the mural even with my limited knowledge. For example, this is a representation of the return of Quetzalcoatl as predicted by Aztec myth. Note that he is a fair haired white man with a beard which was one of the reasons that Cortés did not immediately get the negative reception he deserved. Some thought he was a returning god. Another form of Quetzalcoatl as the plumed serpent emerges from the volcano.

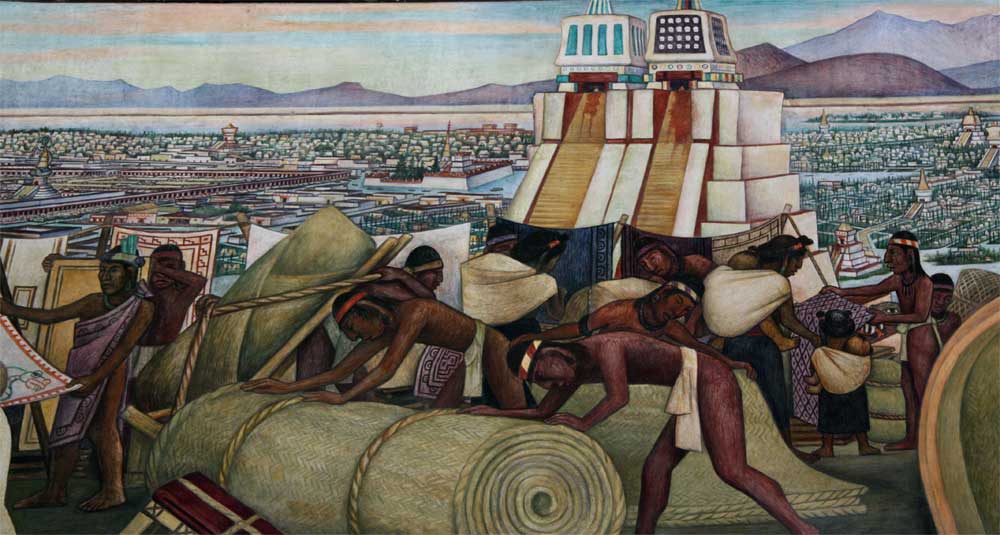

This panel shows the main market in Tenochtitlan before the arrival of the Spanish with the Templo Mayor in the distance, with blood stains dripping down it. Here is a close-up from a public domain photo.

Rivera did not limit himself to the cultures around Mexico City, but includes panels on the Zapotec, Mixtec, Tarascan and others. This is El Tajin near Veracruz with its Pyramid of the Niches.

A closeup reveals the ‘flying man game’, which has evolved into the modern day floridores.

The last panel in the corridor is also the most gut wrenching. It shows the coming of Cortés and the inhuman treatment unleashed on the people of Mexico, including death, slavery and disease in which not only the conquistadors participated in, but the priests as well.

After viewing the murals a few minutes should be set aside for visiting the former Chamber of Deputies if only to see the Masonic eye that looked down on the proceedings.

There are lots of other places around the Centro Histórico I could go on about, this post would get just too long. However, there are a couple of iconic modern buildings that are certainly worth travelling to see outside the centre of the city, both in the University district to the south.

Biblioteca Central & Olympic Stadium

Even though it’s not that old, the Biblioteca Central is one of Mexico City’s most recognizable buildings. Continuing the muralist style of documenting Mexican history Irish/Mexican artist Juan O’Gorman tells the story of Mexico in mosaic stones, that also includes references to astronomy, astrology and other themes. It’s quite simply a one of a kind building that sits well away from other buildings so you can get an unobstructed view of all sides.

Nearby is University Stadium, built in 1952 and host of the 1968 Olympic Games. Once again inlaid stones are used to create a wonderful effect, this time by Diego Rivera. The birds are an eagle and a condor and symbolize North and South America – the first games held here were the Panams in 1955. The figures stand atop the feathered serpent, yet another representation of the god Quetzalcoatl.

When I think of how well this stadium has held up over the years, its overall strength of design and its very reasonable cost, I can’t help but think of that colossal unsightly pile of concrete we built for the Olympic games in Montreal in 1976. A monstrosity from the outset, it rapidly became a Canadian national embarrassment and is barely used today.

One prominent event that I remember well happened here in 1968 when American runners Tommie Smith and John Carlos held their fists high and heads low as they gave the Black Panther salute while receiving their medals. I decide to repeat it, but I’m not thinking about racial prejudice, but rather the stupidity that went into building the Big Owe.

On that low note I’ll conclude my Mexico City mumblings. Next we’re off to Oaxaca and the great archaeological site of Monte Alban.

Many thanks again to Dale, for allowing us to share this post.